Into the Valley Read online

Copyright © 2015 by Ruth Galm

All rights reserved.

Published by

Soho Press, Inc.

853 Broadway

New York, NY 10003

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Galm, Ruth

Into the valley / Ruth Galm.

ISBN 978-1-61695-509-0

eISBN 978-1-61695-510-6

1. Women—Fiction. 2. Conflict of generations—Fiction.

3. Psychological fiction. I. Title.

PS3607.A423I58 2015

813’.6—dc23 2015009876

Interior design by Janine Agro, Soho Press, Inc.

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For Paul

i.

She took the forged check to the bank and cashed it. From there, she walked to the drugstore. She bought tampons and a candy bar (she did not in that moment think of what else she might need) and coiled the rest of the bills in a roll in her bra strap because it did not feel right to have them in her purse. It was a strange bulge at her shoulder, papery and hard, but the sheath was loose enough to hide it. She rode the bus over the hill to her apartment and waited at the corner for the landlady to leave for her daily groceries. It was a basement apartment with no direct light and a dank stone smell no matter what carpets and furniture and ceramic vases of lilies B. had tried to add to it. A small kitchenette had been built in the corner around a dump sink, and she had added a Formica table with two chairs, but the corner still radiated a metallic damp smell. There was a small room next to the bathroom that she’d planned to use as a study or a hobby room, but her only hobby was reading and it made the carsickness worse to read in that cramped space with no natural light, so she left it empty. She knew, in the end, none of it amounted to anything people wanted to hear about in conversation.

In a vinyl bag she gathered a few dresses, underwear, a nightgown, alongside her ostrich-skin purse. She went to her dresser and drew out the velvet box with the diamond brooch she had not touched in two years. When she had everything, she took the bus to a car lot on Van Ness. She had seen the Mustang for sale for months, glittering blue in the bright fog-bleached light, the elongated trunk like the snout of an alligator, she thought, and the body just as slinky and low to the ground. It was a V-8 engine, the salesman warned her. “You don’t know what kind of power an engine like that has. Out of nowhere, you’re flying.” He tried to sell her a Chevrolet, what he called a “more appropriate” car, or a Chrysler, a car “more for someone your type,” but she excused herself to the ladies’ room and extracted the exact amount for the Mustang from the largest bills in the bra strap.

She got behind the wheel and backed out self-consciously as the salesman watched. The steering wheel was large in front of her, hard thin metal and tight plastic coating. The engine jumped at a touch to the gas. As she made her way carefully out of the car lot onto Van Ness, she did not even think of it as leaving, only “going away.” She drove through the city and east across the bridge and wanted simply to put the relentless appeal of the water behind her. The freeway skirted green piney hills dotted with cottages. She imagined them filled one by one with women, mothers and housewives, and she wondered very genuinely how they filled their days, whether they arranged to come down and buy vegetables and attend luncheons or preferred to stay in the cottages as long as they could. She switched on the radio. A song was playing that had played at her first high school dance, and she remembered the peach satin dress and the perfume her mother dabbed at her wrists and the Brylcreemed boy, and for a moment she was taken with the same abstract hopefulness she’d had that night. That something she’d been waiting for would arrive and overtake her. But when the song ended, a commercial jangled on and she found only rock and roll on the next two stations, until finally she flicked the radio off and listened instead to the asphalt breaks beneath her.

She left the green mountains and followed the freeway along the bay, the water seeming never to recede, snaking ever inland. Finally she came to another, smaller bridge and there was no water after that. She felt an inexplicable relief. There were a few houses on the side of the freeway and a roadside nightclub with unlit neon palm trees on its roof, and then suddenly she was in the “golden” hills. They were a sere, sad blond. As the Mustang took the grade through the treeless, waterless land, she did not think of the money at her shoulder or the possessions she’d left behind or her secretarial job at the law firm to which she would not return. When she reached the top of the hill, she took her foot off the gas and coasted downward to the flat valley below and thought of nothing.

ii.

The teller had asked her, glancing at the ostrich-skin purse, if she liked the new tapestry handbags. “They’re like something out of Mary Poppins,” B. had said. The teller nodded in agreement. She had beautifully applied shimmer eye shadow. She counted the bills out sharply and brushed back a lock of washed-and-set hair. The first bank B. would never forget because of these details and because of the first flush of expansive coolness. The lines and the marble and the calm suffusing her. She had smiled at the soignée teller and breathed without spinning and pocketed three thousand stolen dollars.

iii.

“Did you like the new salon? Do you have a date this week?”

Her last conversation with her mother had been exactly like the others.

“I’ve decided, by the way, that I really prefer the pearlescents for manicures.”

Underneath, the carsickness had drummed as though to seam apart her skull. She answered the questions by rote, and through the drumming an indistinct thought pulsed, as blurred and throbbing as the pain: There must be another conversation they were meant

to have. Some other point to which they could apply their exchange.

“Are you not feeling well?” her mother asked.

“No.”

“Be sure to take some air. It’ll brighten your skin.”

And with that, B. had hung up the phone.

iv.

She rolled down her window. Heat blasted her cheek. She exited the freeway and took a road next to some railroad tracks, rusted boxcars abandoned in a long chain.

The wind whipped through the interior, smelling of vinyl and exhaust. She stepped on the gas.

The irony was that she felt the carsickness less in the car. The irony was that the carsickness had nothing to do with actually being in one.

She drove past a lone barn newly painted white and a couple of one- and two-room shacks next to the road, canted picket fences lost in tall grass, dirty old trucks in the driveways. She passed the brown skeleton of a structure, not burned but somehow bared to its dark wooden bones, ringed by no trespassing signs on trees all around. It looked to her in its openness like an ancient place of worship, and she felt a brief urge to stop and sit inside its timbers, but she drove on. A sign read 60 miles to sacramento.

She could go see the capitol. She knew dimly that she would not. She knew dimly that she would never go near another city again.

v.

The valley was because of the man on the bus. She tried always to smile at people in public as her mother had taught her, to look polite and receptive, and they mistook this for an invitation to unburden themselves, when in fact she did not really even want to talk. When he found out she was from the East, the man told her about the long table of land just beyond the mountains and bay. “Nothing happens there. Not one thing.” That’s why, he explained, the easterners never even knew about it. “No pretty scenes, no trees. Just flat. I won’t go back in a million years.” She could see in the man’s featu

res—he was young with large pores glazed in oil and jagged purple veins on his eyelids—something strained and unbalanced. His eyes blazed. He began to mumble. “But I’m safe here, I really am.” B. listened politely for a few more seconds, then got off the bus two stops before her own.

And yet, since the encounter, her thoughts had often drifted to this valley. She imagined that in this long unvarying plane, all the contradictions of the city might fall away. That its bareness would reveal something, provide an answer she had failed to acquire. A place of unvarnished truth to which she must go.

Because it was no longer just the dirty young people in the city who disturbed her. In the restroom at I. Magnin recently, she’d encountered a mother and her teenage daughter. The girl with clear breasts and long legs, as tall as the woman. But the daughter was trying to pull her skirt off. “I’m not sure I want to be wearing it all day,” she said. “What if I get cold? What will I do?” The mother hushing and soothing her, keeping the girl’s hands from the skirt while the girl shuddered. B. washed herself quickly, but the mother looked straight at her, voice harried: “She’s only ten. She looks older, but she’s only ten.” B. had nodded and run out.

vi.

What she had not thought through were the logistics. She had not considered how in this tabula rasa she would find the banks. This new state of affairs, this new exigency, she did not question. She only knew she would find them.

vii.

She had renamed herself “B.” after college. She thought that was the beginning of the problem: she’d never felt like a Beverly, never known what a Beverly should want to do. The singsong syllables and the lift at the end like a promise made without her agreement, disorienting her. So she’d erased it. People heard it as “Bea,” and that was fine with her. As long as she could think of herself as B., something opened up, went blank in a way she could tolerate.

For a time.

viii.

The paper sliding across marble. The tellers’ anodyne voices.

Later it was all spoiled. By the glint of the knife, the blood, the expression on Daughtry’s face as she drove away.

But by then it no longer mattered.

ix.

“Because you’re a good girl, they’ll like you. Because you look normal and you act normal and you’ve done up your hair and you’ve walked in the right way, with class, you’re gonna fool them blind.

“Because I’ve always told you: you’re a good, classy girl and that won’t ever change.”

I

&$9

1.

The car was low on gas. She had not checked the gauge before leaving the lot and she flushed at the thought of the salesman making a joke of her. (No, she had not wanted a Chevy or a Chrysler. She knew this instinctively, although she might only have been able to say it was the look of the car. Something strong and sharp in the Mustang that pared it down to a single purpose, an inarguable direction. She’d never considered owning a car before. The subways and elevateds in the East had obviated any need, and perhaps, more importantly, owning her own car had seemed somehow unseemly. The women in advertisements lounged around cars in feather boas in the company of tuxedoed dates or carted bags of groceries to the back of a station wagon. And so she had tried to put the thought out of her mind, like some lurid afternoon fantasy, but the empirical beauty of the Mustang had stayed with her, and the car was the first thing she thought of after the check.)

There were no buildings in sight. The July heat made her arms and back sweat, moistening and drying and moistening again. Her left arm turned red in the sun. The city never got hot. Even on the warmest days, she shivered, her toes chilled. She wetted her dry lips and tried to put the anxiety about the gas out of her mind, and when she began to see the first rows of fruit trees, she turned into a dirt lane and parked.

Hundreds of peach trees. She rolled down her stockings and took off the bone-colored heels. The ground was dry and hard, the trees not high but in full leaf, crammed with hard orange peaches. She walked until she found a good spot to sit down. The tree was uncomfortable to lean against and the branches too low, so she lay all the way down on her back and tried to relax. A hot day in her childhood, she had snuck into a vacant lot and lay hidden and cooled in the overgrown grass, among the sounds of cars and birds and cicadas. She’d been convinced of the fact she was erased from the world and breathed easy and fallen asleep. She could not remember another day like that since.

She ate her candy bar, moving her tongue along her teeth for the chocolate and clumps of coconut, and pondered the sky through the peaches. Her throat was dry. She had nothing to drink. It was somewhere after one o’clock on a Tuesday and no cars passed. She tried to keep lying as she had in the vacant lot those years ago but the dirt was hard, and she was not hidden, and eventually she went back to the car and drove on.

She passed a horse corral. No people seemed to be around anywhere. The sun blazed on the animals, their heads bent under the heat, their bodies a liquid brown. They seemed to B., in their unconsciousness, in a state of total equanimity. After the horses came a stretch of dry, uncultivated land and then finally there was a gas station.

She filled up and went to the small bathroom at the back of the building. She saw that the whole back of her dress was dirty. The ivory had not been a wise decision, not for driving or sitting in the dirt, not for the second day of her period. Her underwear had spots of blood where her tampon bled through. She never paid enough attention to when her period might arrive and so was never prepared. And when it did come she seemed, irrationally, to disbelieve that it could require more than one or two tampons. That the blood would run on and on for so many days. She was invariably left with soiled underwear and bloody fingers. She took out the tampon and put another in and folded toilet paper over the blood spots. She went inside the store to pay for her gas, not touching the money in her bra. In her purse was a compact, a gold tube of lipstick, gum wrappers, aspirin, a few crumpled bills, and the checkbook.

A middle-aged woman with bleached hair looked at her blankly from the cash register.

“Do you have a water fountain?” B. asked the woman.

The woman did not acknowledge her question, just put down her magazine and went back behind a gray door and emerged with a paper cup of water.

“You on your way to Reno?” the woman asked.

“No.”

The woman looked annoyed.

“Do you sell maps?” B. asked.

The woman flicked her chin toward the back of the store. B. walked to a revolving rack. She picked up a map of the state. “Do you have anything just for the valley?” she called to the woman.

“The ‘valley’?” The woman frowned. “That’s all we have over there.”

By the time B. returned to the counter the annoyance had set into the woman’s features and she pushed the change toward B. and went back to her magazine without looking up again.

B. laid the map across the passenger seat. Hundreds of black names on pastel. She’d only wanted a small patch to concentrate on, just a piece. She folded the map up. The heat in the car and the smells of hot metal and plastic drugged her. She closed her eyes and leaned her head back against the square seat.

She must have fallen asleep because next the woman from the gas station was rapping at her windshield. “There’s no loitering here,” she said. “Can’t just park all day at the pumps. We got other customers, you know.”

B. rubbed her eyes. The woman glared at her. B. looked around; there were no other cars. “I’m sorry. I guess I was tired.”

The woman crossed her arms, the tanned skin draping.

“Is there a bank somewhere around?” B. asked.

“Go back to Suisun City or on to Rio Vista. There’s nothin’ in between.”

For a moment B. thought the woman said something else under her breath. But the woman only continued to glare from behind

the sagging arms and B. had no way of knowing if she was right.

When she came on Suisun City, the small main street and the pale tiled buildings were quaint but the marina behind the town startled B. Just like that, a row of boats in blue-brown water, masts bobbing against the flat yellow. She felt suddenly that the bay was following her, leaking out in a last menacing grab through the marsh stalks.

She jotted a random amount on the check.

“Good afternoon, ma’am.” The pretty teller standing among the calm straight lines and muted oil paintings.

“It’s ‘miss’ actually.”

“Oh, I’m sorry, ma’am. I mean, miss.”

But the cool expansive feeling still came. B. felt so light and cheerful afterward, she considered shaking the girl’s hand, then thought better of it. As she walked back to the Mustang, the odd, misplaced marina did not disturb her in the least.

Back on the road the heat and sleepiness were too much. She searched for a motel and had to return to the freeway to find a motor inn with a billboard of a bikini-clad woman diving into a pool. B. did not turn on the air conditioner when she got inside the room, just let the heat melt over her as she lay on the bed.

She took the money out of her bra strap. It was now at least a dozen fifty-dollar bills; she had no interest in counting them. She rifled through the vinyl travel bag, pulling out for a moment the velvet box with the diamond brooch, then replacing it. Instead she took out a bottle of nail polish.

The room was darkening but she left off the light. She thought of nothing but smoothing the pale iridescent pink from the brush, of the nicely piquant smell. She’d watched her mother at her vanity making her toilette, the French word she’d taught B. for pinning her hair, applying her lipstick, dabbing a crystal perfume bottle at her neck. Each gesture accruing to her some invisible potency. Her mother had once given her the last tortoiseshell compact of her favorite face powder, a discontinued line, and B. kept it intact and untouched like a totem, unsure what might happen if she finished it.

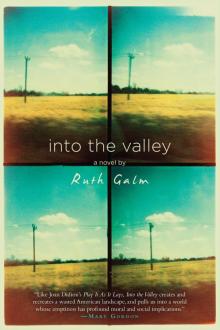

Into the Valley

Into the Valley